The perfect job doesn’t exist. There’s no role in which you’ll be lit up by each and every task. By desperately searching for one you’re fighting an unwinnable fight against the universal laws that govern the nature of work.

I learned this firsthand after slaving away on Wall Street until I did my best Andy Dufresne-like escape from Shawshank and landed my dream job in crypto that checked every single box for my ideal role and work environment.

And yet, something was missing. I’d show up to work, complete my tasks for the day, and still feel like a widening gap between how I felt and how I wanted to feel.

I spent an inordinate amount of time trying to figure out what was wrong. It wasn’t until I came across the prescient advice from a 2,500-year-old Chinese philosopher that I concluded it wasn’t my job causing the unhappiness—it was my expectations for the job.

I was over-indexing on what it means to be in a fulfilling role, believing that every second spent tapping a keyboard or taking Zoom calls is meant to bring a smile to my face.

But I realized that this idealized portrayal doesn’t exist. And that’s okay. It doesn’t preclude you from a happy, fulfilling work life where you relish the opportunity to complete your daily duties, regardless of what that entails.

You just need to find meaning in the greater mission of what you’re working towards, not the individual tasks themselves.

Escaping Shawshank

After graduating from the University of Richmond, I moved to New York to begin my career in banking. This was the path I was steered toward from my upbringing in middle-class suburbia all the way to business school. Teachers, mentors, peers—all seemed to think that I should use my analytical proclivity to pursue a degree in finance and math so I could learn about the business of money. That way, I could make a lot of it. Which, of course, was the goal right?

It took me all of a month to realize that this was a lie. My days were filled with menial tasks in service of extending billions of dollars to large corporations I didn’t care about in a “show-face culture” that necessitated lingering in the office until my superiors left. I felt imprisoned, suckered into a bait-and-switch between the tantalizing allure of investment banking and the harsh reality that fell woefully short of expectations.

While I struggled to get excited about moving numbers around on Excel spreadsheets, the problem wasn’t solely the work itself. My aversion stemmed from this hidden agreement I tacitly signed where I had to be a different person when I walked into work versus who I was for the rest of my life. I was an affable, fun-loving guy with a deeply contemplative side, insatiably curious about the human condition with a penchant for spiritual inquiry and the exploration of life’s greater questions.

But when I stepped into the office, it was like being thrust onstage to a dystopian theater set that reeked of conformity, shallow ambition, and cheap coffee for a play I was forcibly cast into. I had to put on this act of Jack the Banker where I had to wear fancy clothes I didn’t want to wear, read Wall Street Journal articles I had no interest in, and spoke a formal jargon I’d never use, all so that I could return to my apartment after work, briefly step out of character to be me for a short time only to go back for another 15-hour rehearsal the next day.

The dissonance was excruciating. I wanted to be real with the people around me—my coworkers, those who I was spending the vast majority of my waking life around.

Did they also feel this suffocation of authenticity? Were they haunted by the prospect of doing this for 40 years only to realize they never truly lived? Did it infringe on their ability to forge lasting, meaningful connections, or were they comfortable with the pervasive loneliness and shared melancholy that permeated down the skyscrapers of Park Avenue?

I sensed I wasn’t alone. It felt like no one really wanted to be there. I could hear it in coworkers' voices when they spoke about their next vacation, like the hollow echo of a prisoner counting the days until he was released.

It was even worse when they’d get back. I’d listen to a mechanical recounting of a weekend in the Hamptons with a few colleagues eager to distract themselves, offering a short reprieve until the shared reality of work would return, booming like a command from the warden to get back to their cells.

I had to get out. I was only a few months in and every fiber of my being was screaming that this wasn’t the path for me. Thankfully, I knew what was.

My interest in the nascent crypto industry was fast approaching an obsession. I’d first caught wind of it in 2012 from my older brother, a prototypical cypherpunk libertarian, wary of big government, an advocate of free markets with a rebellious, tech-focused bent. I never gave it the time of day, joking I had other things to worry about than magical internet money. However, a steady drip of articles and subsequent conversations were enough to convince a broke college kid to spend $600 of his first intern paycheck on one of these bitcoin things.

While this gave me skin in the game, it wasn’t until I graduated that I made the conscious choice this was a field worth learning about. Once I did, I was captivated. It ignited a spark of intellectual stimulation that tied together disparate fields—from macroeconomics and game theory to cryptography and distributed systems. When juxtaposed to the monotonous work I was given in my cubicle, it became abundantly clear where my interests lied and the industry I was meant to be working in.

Down the rabbit hole

Instead of poring through companies' financials like a good junior banker, I furiously consumed as much content as I could scour online, engrossing myself in a rigorous self-guided Crypto 101 course that began with the basic origins of money. I wanted to understand how and why we came to use the fiat money we know today.

My readings led me to an island called Yap, a small island in the West Pacific, that had been using massive Rai stones as currency for centuries–which seems absurd–but is it really any more more absurd than 30 million people using paper that says “Venezuelan Bolivar” and loses 98 percent of its value every single year?

Before I knew it, I was LARPing as a computer scientist and reading up on the first experiments with digital money that started in the 1980s—DigiCash, E-gold, B-Money, Bit Gold, all started by hardcore academics and renowned cryptographers. Some didn’t make it past a white paper while others ended up facilitating billions of dollars a day before being shut down for one major reason—what’s known as the Byzantine General’s Problem.

This distributed systems challenge involved the coordination of independent parties when no individual could trust one another. The early digital cash experiments couldn’t figure out how to solve this—and it resulted in their demise. However, Bitcoin found a solution by incentivizing people around the world to store digital copies of the entire transaction history, removing any single point of failure.

Keep in mind, this was during the 2017 crypto bull run, during which the media was making crypto out to be nothing more than a get-rich-quick scheme. Meanwhile, under the hood, Bitcoin was a novel technical breakthrough that effectively solved a decades-old computer science problem while also addressing the pressing need for a decentralized, inflation-resistant store of value.

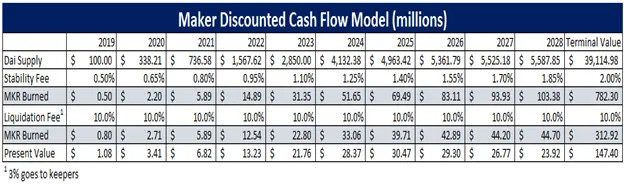

And that’s just Bitcoin, the first cryptocurrency, which I realized was a misnomer for the industry since currency was but a small fraction of what was going on. In fact, most tokens were not intending to usurp bitcoin but instead acted more like equity in a cash-flow generating business.

For example, I began researching a project called MakerDAO that sought to disrupt the industry I was in by creating decentralized credit markets. The native token $MKR provides governance rights and a claim on cash flows. In the same way I would analyze a company we were syndicating a loan for, I created a discounted cash flow model for this crypto network to assess its value. My estimates turned out to be pretty accurate as seven years later it, there are over $5 billion in loans generating $250 million in annual revenue.

My research into decentralized finance was a welcome alternative to the closed-door system I was a part of, rife with conflicts of interest that had brought the world economy to its knees only 10 years prior during the 2007-08 financial crisis.

To highlight the contrast, there’s a scene from The Big Short where Christian Bale’s character spends days sifting through mortgage papers to understand the loans backing these complex financial instruments that banks were peddling on Wall Street. He discovered they were nearly worthless but through financial engineering, the risk was heavily obscured.

With MakerDAO, this would never occur as it would be like if these papers were all in a public database anyone in the world could query in real-time to understand without a shred of doubt the exact composition of every individual loan along with all relevant metadata on the risk entailed and collateral backing the system.

A true zero-to-one innovation.

And crypto goes beyond just money and financial services. It enables core internet infrastructure such as compute, storage, or even vital components of the AI stack including data collection, model training, and inference—all in a similar transparent, trustless environment. This afforded the potential to solve many of the problems created by Big Tech such as data privacy and censorship issues while providing services at a cheaper price than web2 alternatives.

Crypto started feeling like an inevitability. I’d crossed the chasm. I was fully enamored by the industry and willing to do anything to break in.

Finding my way through the Third Door1

There was one issue, however. I was early. There weren’t many entry-level jobs at the time, especially for someone non-technical. I spent hours scrolling through job boards, attending every meetup in the city, all to no avail.

It wasn’t until, like a message from the heavens, I came across a blog post from the CEO at Messari, a startup aiming to build the “Bloomberg of crypto” that I saw a way in. It may as well have been addressed directly to me:

If I want to have any chance at writing more regularly while starting a new company, I need help. And lots of it.

Fortunately, you, dear target audience of 23–27-year-old-entrepreneurial-fintech-geniuses-who-love-crypto, are looking for a way to break into this industry, but you aren’t a hard-core systems engineer.

This call to arms was exactly what I needed. And the message was simple: Start writing. Do it for free. Publish it for the world to see.

And that’s what I did. For the next year, I grinded away, showing up on stage in my business-professional costume, acting out my scenes, speaking the corporate lingo, and doing (barely) enough to get by.

Meanwhile, I secretly spent the majority of my time devouring every bit of crypto content I could find online, publishing my thoughts on Medium2, and helping Messari build a library of content along with a few dozen “community analysts,” as we were known, who were crazy enough to do unpaid work in our free time.

It wasn’t easy. I had a quantitative background and little writing experience. But I improved with time and repetition, stepping up from simple articles about digital gold to more complex theses on decentralized governance and valuation frameworks.

I continued applying for every research role I came across and was interviewing for a startup research firm I thought could be the one. For the final round, they wanted me to write an in-depth investment thesis and get it to them in ten days. The only problem was, I had a trip planned to Vancouver before what I knew would be a particularly grueling week at work.

I wanted to write my magnum opus that would leave them without a semblance of uncertainty who the right hire was but I knew I wouldn’t have the time. I lamented this situation to my friend I was visiting, someone I confided greatly in as he always seemed to have useful, unorthodox advice.

I’ll never forget the mischievous look in his eye as he proposed

“What if you tell your company you lost your passport and can’t make it back? Then you can use the rest of the week when you’re back to write the report.”

At first, I audibly chuckled, dismissing the seemingly preposterous idea before rebutting that I couldn’t. It felt insane, reckless, even morally wrong.

But when he candidly asked why not, I didn’t have an answer. I knew I had zero future in banking and any desire to do right in my job was nothing more than a vestigial sense of propriety I felt I owed to The Default Path.

I opened my laptop, crafting an elaborate tale about leaving my backpack in my friend's car that got broken into leaving me passportless in Canada, and how it would take a week for me to get a new one from the embassy. Shortly thereafter I got a response with condolences and understanding, assuring me they’d manage in my absence.

I flew home and spent 12-hours days all week on this report before sending in my finest work.

Crickets. Weeks passed and I never heard back from the company. The crushing disappointment was tempered by an indomitable resolve. I started sending that report with my resume to every job I applied to including Messari as they were looking to bring on their first full-time analyst.

A month later I got the job.

It was a dream come true. Everything I had previously been doing on nights and weekends I was now getting paid to do (albeit earning half of what I made in banking). And I got to do it from a 10-person WeWork space with beer taps in the lobby that I could walk into with flip-flops.

I was a professional curiosity-satisfier—a kid in a candy shop of learning—spending my days researching any topic that piqued my interest. And I had direct access to nearly every entrepreneur in the industry along with a megaphone to reach hundreds of thousands of industry participants.

I would get real-time feedback from my coworkers who had similarly left high-paying corporate jobs, were equally crypto-obsessed, and hell-bent on creating a more open, equitable, and decentralized future.

What’s more, I genuinely felt a strong alignment with the company’s mission to bring greater transparency to the industry. If we were ever going to graduate from impassioned tinkerers and hobbyists to legitimate contenders on the global stage, someone had to create an institutional-grade data and research product. And if I had any say in the matter, it was going to be this team that showed up well-caffeinated to an office the size of a walk-in closet on 42nd and Broadway, raring to bring this vision to life.

What more could I want? I had everything I’d hoped for and some.

The grass wasn’t green enough

Over the next 18 months, the industry entered its next bull market. Bitcoin eclipsed a $1 trillion market cap in the post-COVID era as investors sought a safe haven from excessive government spending and monetary debasement. My original thesis was playing out before my eyes even faster than I’d expected.

This provided strong tailwinds to Messari, as well as to my own career. My research background proved invaluable as it gave me the requisite knowledge to inform the company’s strategic direction. I saw an opportunity to build an outsourced investor relations service for crypto teams to create standardized quarterly financial reports. I pitched it to close partners we worked with and it immediately resonated. The next thing I knew I was given the reins to lead business development for this rapidly growing revenue line that was finding product-market fit. My career was taking off and as it turned out I was making way more money than I would have if I stayed in banking.

By all measures, things were going well. Really well. Better than I could have imagined when I first started. We had raised $60 million over several rounds of funding from big names on Wall Street like Point 72 and other reputable venture capitalists. We grew headcount from 10 to 150. And most importantly, we were bringing to life all that we set out to do when I first started.

And yet, while everything was going great, my inner world didn’t reflect that. The novelty and excitement of the early days gave way to the chaos of startup life, replete with the pressure to succeed. I developed a growing unsettling feeling that something was off.

There would be days I would wake up, sit down at my laptop, and feel like I was doing a chore. The hours would drag on, I’d be getting work done, but it didn’t light me up like it used to. I felt like I was wasting away, beholden to the tyranny of a screen as I daydreamed about all the things I’d rather be doing like burying myself in a good book, exploring my inner world in meditation, immersing myself in nature, all of which sounded more exciting than creating onboarding documentation for a new hire, updating our CRM, or whatever the day's task ended up being.

I longed for more—something that brought me joy like it did when I’d first started.

So I ran a thought experiment. If I had a magic wand and could create the perfect environment for success and happiness, what would it look like?

I spoke with friends, wrote in my journal, did everything I could to paint a picture of this ideal future state. As the image on the canvas began to take shape, it became clear I wanted to stay in sales at a fast-growing, mission-aligned company in crypto. I wanted to be around brilliant people. And I wanted to feel aligned—like I had a higher purpose to my work and my efforts played a consequential role in shaping that vision for the future I believed in.

The painting looked exactly like my current state of affairs. As much as I tried, I couldn’t think of a better place to be. But I wanted to feel differently. So why wasn’t I happy?

If it wasn’t the job that needed changing, it must have been me.

Discovering the true nature of work

I had to go inward. I started brainstorming what it was that I was doing that led to my unhappiness. For the life of me, I couldn’t pinpoint the issues. I was stymied. Afer all, all I was doing was looking for fulfillment in my daily tasks.

Sometimes, help comes from unexpected places. And this time, it came from a book on Taoist philosophy, a genre I’d uncovered down my non-work rabbit hole of spiritual literature to quell the more existential questions I had. In it, I found the much-needed advice on the very modern problems of a mid-twenties director of sales for a crypto research company struggling to find meaning from the ancient Chinese philosopher Zhuangzi:

An underling’s service to a boss is responsibility…it cannot be avoided anywhere in this world.

Thus I call these the great constraining obligations… to be reconciled to whatever may be involved in the service you must render to your boss is complete loyalty. But further, in the service you must render to your own heart, to know that nothing can be done about the sorrow and joy it unalterably puts before you, and thus reconcile yourself to them as if they were fated—this is completely realized virtuosity.

Being a subordinate, there will inevitably be things you cannot avoid having to do. Absorb yourself in the realities of the task at hand to the point of forgetting your own existence. Then you will have no leisure to delight in life or abhor death. That would make this mission of yours quite doable!

I had to put the book down mid-page. I was struck by the implications. While the work itself has changed since Zhuangzi’s time, the nature of it remains the same in that most tasks are borne out of necessity, not desire.

Could it be that my search for fulfillment in minute tasks was the reason I was unhappy?

When I fully grasped the profundity of this, I felt like Sisyphus if the gods had let him put his boulder down. I could find comfort in the banality of my tasks, relieving myself of this self-induced unhappiness. I could treat them like a meditative exercise where I stopped making them out to be something they’re not and could immerse in it solely for the sake of accomplishment—not just to derive some external value.

Integrating a fresh perspective

Another year went by, this time spiraling the industry into a deep bear market. Crypto is inherently cyclical—it places public market asset prices on early-stage venture businesses, which leads to exaggerated highs and lows. But these highs were magnified by excessive leverage and brought even lower in part to an Enron-scale fraud.

While the world was burning around me, I remained unfazed. My conviction in the industry had never been higher. I saw the lows as a necessary cleansing, a forest fire to burn away the excesses, providing fertile ground for the remaining entrepreneurs and investors.

As for my work, I experienced a radical shift in the emotional texture of the day-to-day. Even though the work itself hadn’t changed, my relationship with it had. And it made all the difference.

Whereas before, if I wasn’t working on a lucrative deal or putting together an interesting strategy presentation, I would get in my head. I’d feel lost, like a mindless drone wasting away, longing for that picturesque work life I’d see on social media.

Now, I saw those ostensibly banal tasks for what they were–a critical piece of what was needed to move Messari’s business forward, advancing step by step towards actualizing the grand vision of the future I knew was possible for this industry. The previous existential dread I harbored dissipated entirely, replaced by a clearly defined purpose and tight linkage between my efforts and the original mission I embarked on.

Those same onboarding docs or CRM management suddenly had new meaning. Even my household chores took on a whole new life. Once I absolved myself of the unrealistic expectations around the nature of work, I was free to see them as opportunities to accomplish the necessary tasks in front of me in order to reach my ultimate goals. And that I could do with a smile on my face.

I still occasionally work long hours. I still end up with tasks I’d love to pass off. There are still days I long to sit down with a good book or explore the pristine nature of my new home in Puerto Rico. But I’m no longer bothered by it. I know there’s a time for leisure.

But until, then there are simply things I need to do.

Stop looking for fulfilling tasks

We’re fortunate in today’s world to have an abundance of money-making opportunities, many of which were unimaginable for the majority of human history. This allows us to be selective and choose work that aligns with our interests.

However, there are unintended consequences to the relentless pursuit of “doing what you love.” in that it inadvertently skews your perception because reality never conforms to those expectations.

The result is a growing disparity between the day-to-day job and your idealized conception of what work life should be. It leads to prolonged unhappiness and a perpetual “grass is greener on the other side” syndrome.

This idealized conception doesn’t exist. And that’s okay.

Whether you are your own boss or your boss is delegating work to you, there are inevitably tasks that come up you’d prefer not to do, but, in order to be a productive member of society, they have to be done.

But there’s value in those menial tasks–the ones that you wouldn’t be doing in your perfect world. The ones that don’t require much thought, where you’re not exerting yourself or interacting with others in a meaningful way. The ones that may feel like a waste of time, that don’t bring you joy, but that you do anyway because they need to be completed.

This isn’t a masochistic call to seek work you hate and push through misery. It’s a framework for how to deal with the not-so-sexy things that are part of any job.

You don’t need to run from the bland, boring, even occasionally painstaking tasks—doing them doesn’t prohibit you from finding deep joy and meaning. In fact, they can help you garner a profound appreciation for work. There is a certain beauty in obligation, an honor in perseverance, and a longstanding happiness that comes from loving that which appears unlovable.

To do so, find fulfillment in the higher purpose of your job, not the individual tasks themselves.

Shoutout to Lawrence Yeo, , and the editors at Every for helping with feedback on this essay.

A reference to the book The Third Door with the idea being that Life is like a nightclub–there are always three ways in: The First Door, the main entrance, the Second Door: the VIP entrance, where celebrities slip through, and the Third Door that no one tells you about where you have to jump out of line, run down the alley, bang on the door, crack open the window, sneak through the kitchen… getting in by any means necessary.

Much to the chagrin of my boss who scolded me after seeing a LinkedIn post insinuating I could get fired for offering investment advice. That didn’t stop me, I just moved to crypto Twitter.

Love that enlightenment quote :)

Totally agree this work-life distinction is a weird one and we should just focus on life, accepting that work, however occasionally mundane, is a part of that!

This resonated with me. Especially the part about wanting to spend more time meditating, in nature, writing… I can’t fit enough meditation into my day right now!

The way out is in, as Thich Naht Hanh said. It’s just so much more difficult than running towards, and outwards.

I really wanted to ‘make a difference’ and spent years in the UN system, NGOs and diplomacy, so a slightly different trajectory. I ended up quitting (and still have no idea what I’m doing).

But I’m fairly convinced that the invention of the career is a recent and sometimes pernicious trap. And also the way society talks about work-life balance is the wrong way to approach this - we still need to be fully taking part in our lives when working. And as you say, embrace the mundanity of some of the less glorious tasks that just need to get done.

Before enlightenment, chop wood, carry water. After enlightenment, chop wood carry water.

Thanks for your writing - look forward to reading more.